I gave a general ChatGPT Agent 27 minutes to be my candidate sourcing agency.

What I really measured wasn’t time—it was attention.

As context: I work at LinkedIn engineering team building AI features for SMB hirers. Out of personal curiosity (opinions here are mine alone), I tried ChatGPT’s new Agent Mode on a made up recruiting task: “Find ~5 event‑planner candidates for a 4‑week, half‑day community market in Cupertino and draft InMail outreach (don’t send).”

What happened:

The agent began by searching broadly—Google, Yelp, Reddit—not just limiting itself to LinkedIn.

I actually liked that: it hints at a future where agents triangulate across public signals and then converge on LinkedIn to validate or enrich candidate profiles.

After I took over and logged in LinkedIn.com, it adapted: ran a LinkedIn people search, experimented with the query vs. the location filter, opened profiles, scrolled (sometimes awkwardly), expanded experience sections, occasionally mis‑clicked into a company page, and recovered.

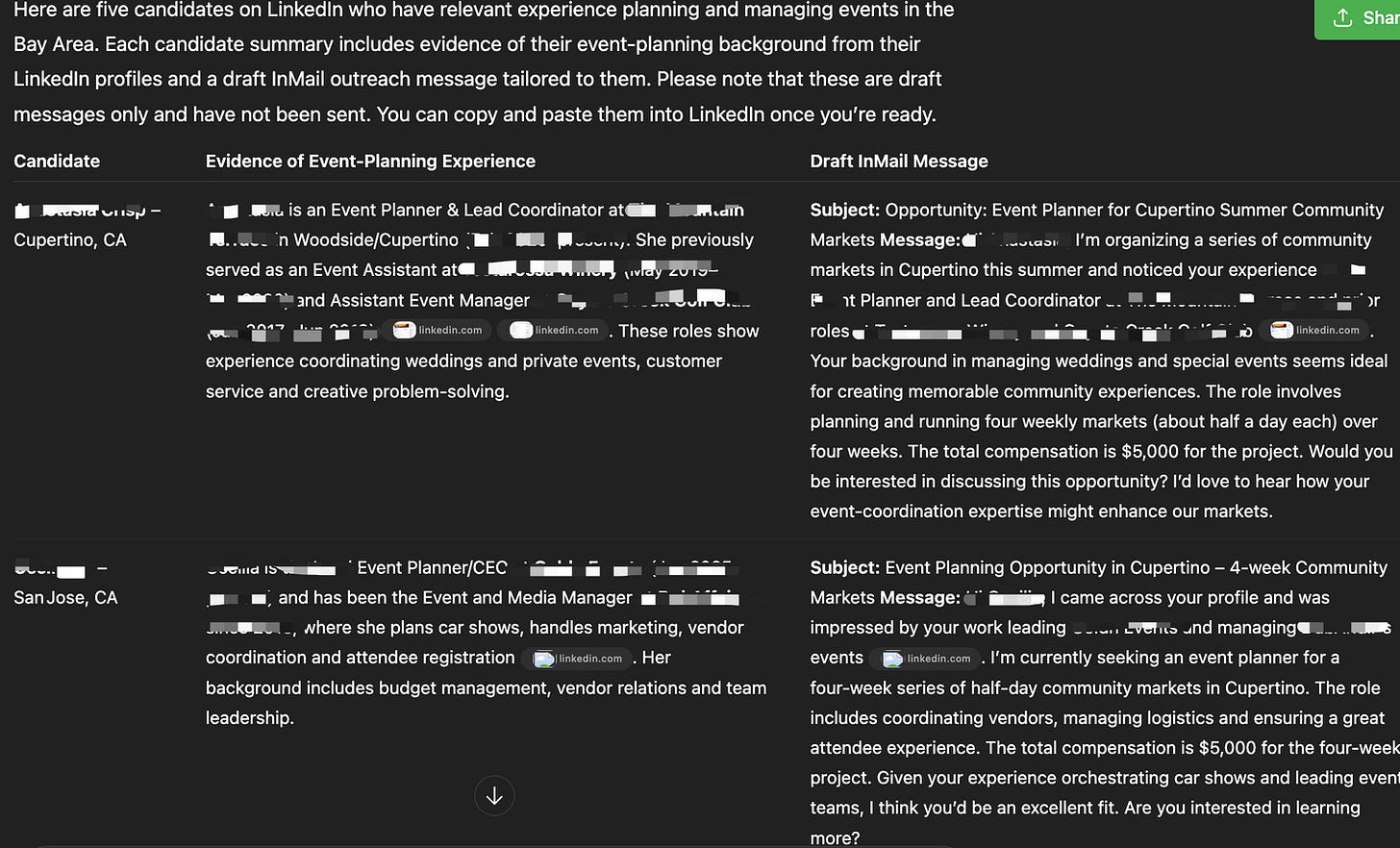

It applied light heuristics (e.g., skipped current students) and ultimately produced five candidates with personalized draft messages (see masked screenshot).

If I did this myself, I’d probably finish faster. But that misses the point. Those 27 minutes were zero minutes of my focused attention. I can go on with other work while an autonomous cursor trudged through the busywork. I’m realizing my productivity metric is shifting from elapsed minutes to attention minutes. Trading more wall‑clock time for less of my cognitive time is a win.

Trust & autonomy:

LinkedIn is a trusted platform, and I’m not in a position to define what level of error is “acceptable” for any customer segment.

In this personal experiment I deliberately stopped short of sending messages.

Still, it’s easy to imagine typical user—after calibrating prompts and reviewing a few outputs—gradually granting the agent more end‑to‑end autonomy. The path to “click send for me” feels closer than I expected.

Search depth:

I asked for five candidates and the agent delivered exactly that—by reviewing the visible top results and selecting five rather than exploring deeper pages.

That’s not a concern to me; with different prompting or continued model improvements it could easily broaden its exploration.

Meanwhile LinkedIn will keep investing in underlying relevance, so both sides of the stack are improving.

The more interesting question:

Who are we building software for now—humans or agents?

The same feature may need two modes.

Manual mode optimizes for interactive speed and human comprehension.

Agent mode might tolerate slower wall‑clock execution if quality, completeness, or compliance go up.

Pricing and metrics assumptions also shift: a $20/month general agent can tirelessly use a product far beyond the “average human usage” many business models were calibrated on.

That could push platforms toward agent‑friendly surfaces (structured data, APIs) and new ways to capture value (outcome pricing, usage tiers, “agent seats”).

My working thesis: most professionals will pay for a general agent and still choose vertical platforms like LinkedIn only when those platforms deliver differentiated value—trust graph, proprietary signals, faster/better outcomes—on top of generic automation.

Curious how others are thinking about “attention minutes” and designing for manual vs. agent modes. How is this changing your roadmap?

Opinions are my own. Drafted with help from ChatGPT.